To B or not to B – Coutts and Mishcon de Reya are B Corps. Should you be too?

The Strand offices of the private bank Coutts, which is now a certified B Corporation

The Strand offices of the private bank Coutts, which is now a certified B Corporation

The wealth manager and private bank Coutts and the law firm Mishcon de Reya have become B Corps – companies that strive to balance purpose and profit.

B-Corp certification was previously associated with brands that have long been committed to environmental and social matters, such as Patagonia, The Guardian and The Big Issue, but now – due to climate change, social justice activism and the boom in ‘ethical’ investing – many brands want to signal their commitment to a sustainable future ahead of the COP26 climate summit.

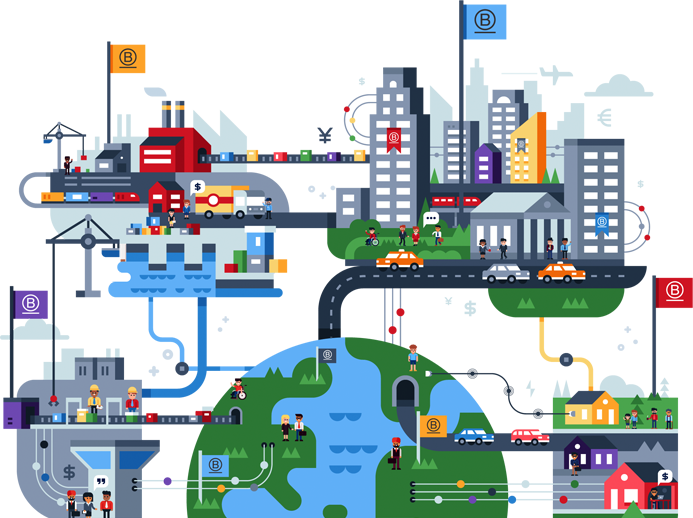

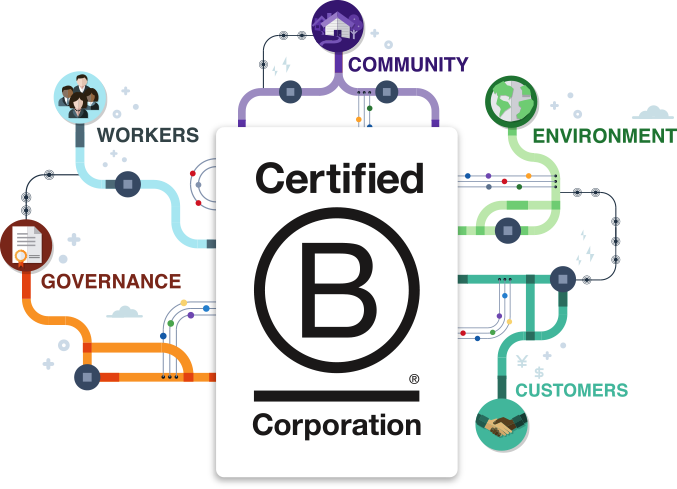

Certified B Corporations – the ‘B’ stands for ‘benefit’ – are legally required to consider the impact of their decisions on their workers, customers, suppliers, community and the environment. Certification has been called the corporate equivalent of the Fair Trade label.

Coutts and Mishcon de Reya are among the latest firms to decide B Corp is the best framework for measuring, improving and reporting their impact but are they right?

The ‘alphabet soup’ of sustainability

Alarming climate warnings from the UN – “code red for humanity” – and social justice protests have led to a gold rush in sustainable investing. Funds that select companies based on their environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance are the fastest growing segment of the European funds market going from seven per cent of all new funds launched four years ago to 46 per cent in the year to date. They are forecast to outnumber conventional funds by 2025.

ESG credentials are increasingly driving not just investment decisions but also employee and customer choices. Consequently, brands are falling over themselves to acquire them. However, there is not yet a universal framework for measuring, improving and reporting ESG performance. Some organizations use the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a structure. Others adopt a bespoke approach hiring ratings agencies to assess their performance and sustainability consultants to show them how to improve before reporting their progress in annual impact reports.

Meanwhile, myriad reporting frameworks – voluntary and mandatory – have been created to help organizations integrate sustainability into their operations. There are more than 30 voluntary environmental reporting frameworks alone.

These acronym-heavy standard setters include the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB) and the Value Reporting Foundation (VRF) – the result of a merger in June of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). There are environmental standards such as ISO 14001, an internationally agreed standard that sets out the requirements for an Environmental Management System (EMS), and ISO 14064, a greenhouse gas protocol. There is also the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), a set of climate-related disclosures aimed at promoting more informed investment decisions, and the Science-Based Targets (SBT) initiative, which helps organizations set climate goals. There are also firms such as Future-Fit, which sets a sustainability benchmark.

The result is a confusing ‘alphabet soup’ of metrics. The fragmented and opaque nature of ESG reporting has led critics to accuse companies of greenwashing and so-called woke capitalism in what has been called by one former hedge-fund partner “the defining scam of our time”. Some joke the best way to improve your ESG rating is to change your rating agency. Meanwhile, the Financial Conduct Authority is so concerned it sent a letter to fund managers in July warning them many new ESG funds “contain claims that do not bear scrutiny”.

CEOs have been calling for government regulation ahead of COP26. This might seem surprising but Fiona Reynolds, who was chief executive of the UN’s Principles for Responsible Investment initiative for nine years, told the FT that many companies would prefer regulation to the smorgasbord of voluntary reporting options.

There are signs that a consistent approach to measuring and reporting impact may be in sight. The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation, which sets global accounting standards, is poised to launch the International Sustainability Standards Board ahead of the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow next month with the aim of creating a universal framework.

To B or not to B

For some companies, B Corp is the solution. It provides a structure to measure, improve and report ESG performance and an external stamp of approval. There are more than 4,000 B Corps in 77 countries. The paid-for certification is provided by an organization called B Lab.

Coutts, known as ‘the Queen’s bank’ for serving the royal family since George IV, said its decision to certify was driven by younger customers concerned about the impact of their wealth. “We seek to bank families over generations,” said chief executive Peter Flavel. “I do think that a younger generation of client coming in is going to want to see that we’re addressing these issues.” Flavel said it took 18 months to achieve certification. Coutts, which is part of the UK-listed NatWest Group, is so proud of its B-Corp status it promotes it on the windows of its Strand offices and the home page of its website.

Coutts is one of the largest UK banking brands to become a B Corp and joins more than 500 other B Corps in the UK, including energy company Bulb, The Body Shop, Freud Communications and the Jamie Oliver Group. Retailers, including Ocado, Waitrose and Boots, are not B Corps but have B-Corp aisles featuring products from certified brands.

Critics of the model say it is a public relations exercise that will be overtaken by mandatory ESG reporting. Advocates say most companies now view sustainability as an important value but those that achieve B-Corp status have gone the extra mile spending time – often up to two years – and money on certification, and submitting evidence to support their claims. They say B Corp closes the gap between rhetoric and reality insulating sustainable companies from accusations of greenwashing and preventing unsustainable companies from making hyperbolic claims. They add that people feel good about working for, buying from and investing in B Corps.

Grain, which advises businesses on their sustainability strategies, chose the B-Corp model for its own business. “I’m a big fan of B Corp,” co-founder Madelyn Postman told StoryCode. “B Corp doesn’t solve it all but it is a very good over-arching framework. It provides a clear and accessible structure and is a globally-recognized badge that is hard to achieve so it really means something to attain it.”

Postman thinks brands are moving towards a hybrid approach in which they will combine two or three complementary frameworks. “There is not one right path,” she said. “For instance, we are members of 1% for the Planet, which means giving 1 per cent of our profits to environmental non-profits each year. We are also planning to introduce an impact report for Grain, actually prompted by our B-Corp certification process, and we will use the UN’s SDGs for that so it’s not a case of one framework or another. ”

Danone North America and some Unilever subsidiaries, such as Ben & Jerry’s, are B Corps and last month the digital consulting firm Kin + Carta became the first UK PLC to secure B-Corp status but, for the most part, public companies have not adopted the B-Corp model with many opting for the UN’s SDGs as their framework for corporate social responsibility (CSR). This may partly be because shareholder primacy is in their DNA and B Corps are legally required to consider all stakeholders in decision-making. When Vital Farm, which produces eco-friendly eggs, went public last year, it noted that its B-Corp status “may result in actions that do not maximise stockholder value”.

There are signs the coveted B-Corp badge may raise a company’s valuation. Mishcon de Reya became a B Corp before pursuing a public listing in London and, in the US, the SoftBank-backed insurance start-up Lemonade became the fifth US company to IPO as a B Corp in July.

It is not clear whether B Corp will become the prevailing paradigm or whether it will be overtaken by statutory reporting. Regulation is likely to happen in stages and the first priority will probably be mandatory climate disclosures from large companies. Until there is a universal standard, B Corp does appear to provide a clear and accessible framework for measuring, improving and reporting impact.

BECOMING A B CORP

B Lab aims to measure a company’s entire social and environmental performance. To certify, a company must achieve a score of at least 80 points out of 200 on its B Impact Assessment – a free, online platform that evaluates company performance across five impact areas (governance, workers, community, environment and customers) – and complete a disclosure questionnaire. The company then submits the assessment for review, provides supporting documents and, if certified, pays the annual fee, which is linked to revenue. The current review process alone takes six to ten months.

A company is also required to amend its Articles of Association to commit to considering all stakeholders – from employees and suppliers to communities and the planet – in decision-making, not just shareholders.

Success is not guaranteed: B Lab says that around one in three that apply will achieve certification. To maintain certification, B Corps must update and verify their impact assessments every three years.

READ MORE

Woke, Inc by Vivek Ramaswamy

Better Business: How the B Corp Movement is Remaking Capitalism by Christopher Marquis

The B Corp Handbook: How You Can Use Business as a Force for Good by Ryan Honeyman and Tiffany Jana

The Big eBook of Sustainability Reporting Frameworks 2021 by ecoact

Winners Take All: the Elite Charade of Changing the World by Anand Giridharadas